My favorite neighborhood tree, a scots pine

My favorite neighborhood tree, a scots pineHello tree.

I don’t actually know you, but recently I’ve been wondering what trees say.

A friend of mine gave me your contact information, so I thought I would go straight to the source.

So here is my question: what would you tell people if you could speak?

In 2012, the City of Melbourne was facing a problem: city trees were declining after a 13 year drought, and there were over 70,000 trees to track and care for1. To help with the caretaking effort, the city began a program to create ways for residents to learn about the trees in their neighborhoods and report issues. Part of this initiative included a practical solution: give every tree a unique ID number… and an email address.

While the intention was for neighbors to flag problems, the ability to write a letter to a tree opened the door to a flood of messages the city council did not expect—thousands of love letters, fan mail, requests for wisdom, curious questions, memories, jokes, and bad puns, all written to trees. The letters are remarkable, moving, and funny:

Dear Green Leaf Elm,

I hope you like living at St. Mary’s. Most of the time I like it too. I have exams coming up and I should be busy studying. You do not have exams because you are a tree. I don’t think that there is much more to talk about as we don’t have a lot in common, you being a tree and such. But I’m glad we’re in this together.

Cheers,

F

Hello Green Leaf Elm,

It’s me again (F). I just got my marks for last semester back! On a definitely completely unrelated note, how do you deal with the constant, relentlessly soul-crushing pain of disappointment after disappointment that characterises our lives on Earth? You must be very old, right? So I thought you might know.

Thanks again,

your friend,

F

Dear English Oak,

I have chosen to write to you given your proximity to the Shrine of Remembrance and that your status is ‘unknown’.

I write about a friend of mine … someone who has reached an intersection in life. To the outside world he has control, but within it can feel like a labyrinth with too many possible pathways, all without much clarity or light.

How can I help him during this time of decision and indecision?

Thank you wise old tree.

Dear Smooth-barked Apple Myrtle,

I am your biggest admirer. I have always wanted to meet you, but tragically, I’m stuck in New York.

I think you are the most handsome tree of them all, tall with an inviting open canopy. I love to just dream of you, the smell of your clusters of white flowers, the sight of your lush, dark green foliage, and feel of your patterned bark.

You inspire me to live life to the fullest, and pursue my dreams; you keep growing despite the terrible tragedies in this world. You are loved and deserve the world.

Love, some person in New York

Dear Rose Gum,

Over the past year I have cycled by you each day and want you to know how much joy you give me.

No matter the weather or what is happening around you, you are strong, elegant and beautiful. I wanted you to know.

Love.

My favorite neighborhood tree, a scots pine

My favorite neighborhood tree, a scots pine

Me with the tree

Me with the tree

Another view of the tree

Another view of the tree

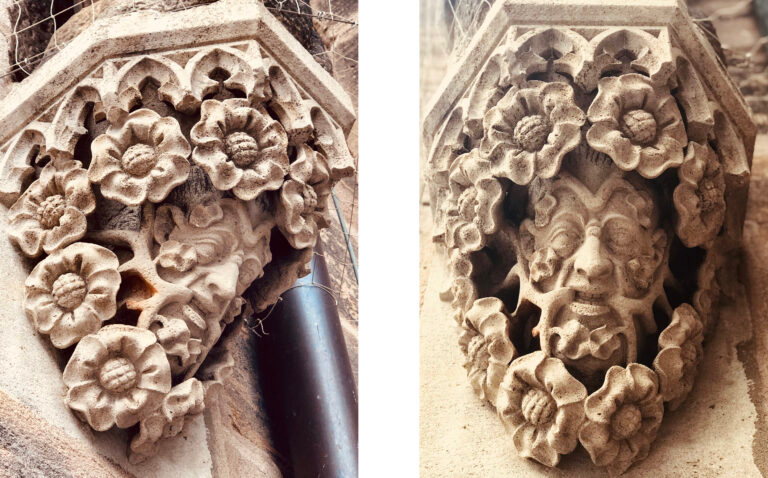

Wild eyes look out from the forest, a head surrounded by foliage, leaves sprouting from nostrils—is he human or vegetation? Is he a spirit of spring or a fearsome warning of decay? The “foliate head” motif—a male face surrounded by or sprouting leaves—is weirdly common as a decorative element in architecture since at least the 2nd century, and examples are found across India, Iraq, Europe, and the UK. It is especially common in European medieval churches, but variations are found in secular and religious buildings over many centuries. When he is found, he seems to live in the margins on pages, in buildings, and in stories, and most recently caused a stir when his visage was prominently present in the margins of a king’s coronation.

An example of the foliate head in architecture

An example of the foliate head in architecture

An example of the foliate head in architecture

An example of the foliate head in architecture

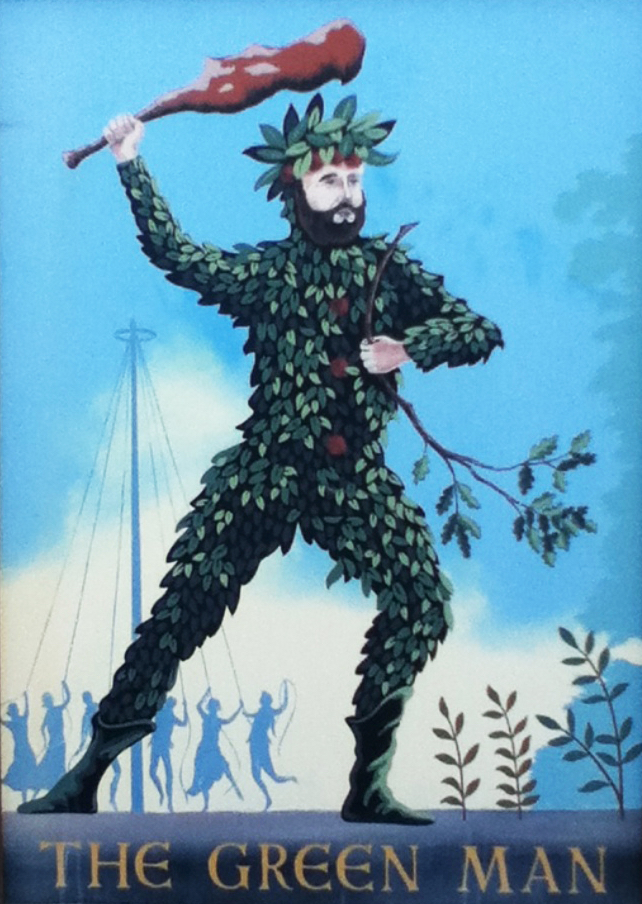

When found in a church, it’s natural to wonder if the foliate head emerged in an ancient myth or belief system, carried through and adapted to a Christian context. In the last century, it’s become common to refer to the motif as the “Green Man,” and there’s a common belief that he represents an ancient nature deity, spirit, or archetype. And yet, despite much debate and research by scholars, there is no clear evidence that reveals a consistent identity, ancient origin, or explanation for his presence. He is everywhere but anonymous. Despite his unknown source, there’s no doubt the Green Man motif is enjoying a wild growth and resurgence in contemporary mythic imagination, and his “remarkable persistence” in the background is a mystery that prompts investigation.

Self Portrait with Leaves (Asleep)

Self Portrait with Leaves (Asleep)

Self Portrait with Leaves (Awake)

Self Portrait with Leaves (Awake)

The Green Man’s mysterious, wordless stare might be interpreted in many ways. On the surface, he might be seen as a suspicious stranger, an outsider looking in at the shelter of our campsite or encountered in the dark forest. From a symbolic perspective, he might represent the exciting and rejuvenating forward march of spring, the sense that after every winter the green summer will flourish again. From another perspective, he brings to mind the images of ruined buildings and old roads, a symbol of the human world gradually decaying and being subsumed by the relentless and inevitable growth of nature. From all angles, he prompts us to wonder: what lives in the boundary between?

Both the story of the Green Man and Melbourne’s tree email system bring attention to the border between the human and more-than-human worlds. In their writing, Anna Tsing and David Abram both reflect on how commonly the world of “nature” is treated as a “backdrop” for the human world, both “enabling conviviality” and being used as a “resource.” From this human-centered perspective the city trees are a resource to be maintained as an element of urban landscaping, and the Green Man motif is “simply a visual joke” playing on the unexpected and often ominous blending of human and vegetable.

A modern interpretation of the Green Man defending the conviviality of a festival

A modern interpretation of the Green Man defending the conviviality of a festival

It may appear romantic to act as though a tree can be reached by email. Trees certainly don’t check their inboxes, and even if they could reply it wouldn’t be in a way we could understand. It may also appear misguided or naive to invent an ancient story for a motif like the “foliate head” that apparently never had one. We might see emailing trees and making up myths as unrealistic tree-hugging romanticism, irrational naivety, or rootless neopaganism—the activity of people searching fruitlessly for meaning in a world where previously reliable sources have been uprooted, fragmented, and are well on the way to becoming compost.

And yet, when given the opportunity, thousands of people act on the impulse to send an email to a tree, and the beguiling visage of the half-man half-plant spirit persists over centuries. When we have the sense—or sensuous technology—to perceive it, perhaps we can hear oak trees sing. And perhaps some myths are seeded long before they’re named. Perhaps a myth that grows wild in the mysterious margins has a good reason to remain anonymous and only glimpse out of the forest, half way between worlds. Perhaps its power comes from its place in the periphery. While these stories may seem irrational or imaginative from the perspective of the human world, when given the opportunity our senses and imaginations might be awakened, and encourage us to reconsider the margin, look from another angle, and notice the animacy of plants, minerals, and other animals.

@modernbiology Does this sound oak tree energy to you? ☺️ I recorded this back in the fall, when the trees had leaves! What a wonderful session with this big old oak 🙏🏽 #oak #tree #synth #musiciansoftiktok #nature

♬ original sound - modernbiology

Koroks, characters in the Legend of Zelda universe

Koroks, characters in the Legend of Zelda universe

In Magic and the Machine, David Abram reflects on his research into the “human propensity for animistic engagement with every aspect of the perceptual world”:

… animistic perception is utterly normal for the human organism, a kind of default setting (to use a technological metaphor) for our species; that in the absence of intervening technologies, the human senses spontaneously encounter the sensorial surroundings as a field of sensitive and sentient powers. Our most immediate experience of the earthly world, and of the myriad bodies that compose this world, is of a multiply animate cosmos wherein no thing is definitively void of expressive agency, or life.

For animism—the instinctive experience of reciprocity or exchange between the perceiver and the perceived—lies at the heart of all human perception. While such participatory experience may be displaced by our engagement with particular tools and technologies, it can never entirely be dispelled. Rather, different technologies tend to capture and channel our instinctive, animistic proclivities in particular ways.

In other words, while we may not say we “believe” a rock, oak tree, or telephone can sense our presence or have their own sense of aliveness, on closer inspection we often act as though they can, and the animate perception we have is consistently directed toward the human-crafted world through our own tools and technology. As Abram writes, we often act as though technology like text and computers can speak with their own voice or with the voice of another person. We often feel we can sense the intentions and expressions of other humans in the places and objects they create. We can sense care in the quality of a crafted object, as a “reciprocity between the perceiver and the perceived” that is distinct from both.

In Kenji Ekuan’s words, “making an object means imbuing it with its own spirit.” In Christopher Alexander’s words, we sense a Quality Without a Name, a degree of aliveness, wholeness, and quiet presence in a place and the activities that happen there. This quality is imbued in the object itself, it does not depend on the maker’s continued presence. When we’re open to receiving and noticing it, we perceive this quality as a distinct “expressive agency” or spirit within and around the body of the object or place.

Our animate perception is alive and well and has only been channeled in a particular direction by human-centered technology. Most of the time, our attention may be focused on the human made world, channeling our “animistic proclivities” toward text and craft and relegating the animism of the rock, oak tree, and wind to the background. But when we expand our awareness into the margins, where the Green Man lives and where new technologies might enable conversation with trees, we experience the wholeness of life with a sense of entanglement, disorientation, and enchantment. To enchant—”in sing”—is to encounter a voice within, to imbue with charm, delight, and mystery.

The Kokori tribe, characters in the Legend of Zelda universe

The Kokori tribe, characters in the Legend of Zelda universe

“The universe is full of magical things patiently waiting for our wits to grow sharper.” -Eden Phillpotts

When a tree gets an email address, a channel is opened in the “wood wide web” that enables an exchange with the tree. For those who have a favorite neighborhood tree, the opportunity to share a message with the tree becomes an “instinctive experience of reciprocity or exchange.” There is no question of whether it’s “real” or not, or if the tree will ever receive the message—the exchange must be attempted when the channel is available, the way water must flow if a dam is opened. While the communication may not be the most efficient or effective, a tree’s email address is an enchanted tool—it expands our animate perception so that we can more easily perceive the life of another and initiate exchange and creative participation.

An enchanted tool: the wind phone (風の電話, kaze no denwa) is an unconnected telephone booth in Ōtsuchi, Iwate Prefecture, Japan, where visitors can hold one-way conversations with deceased loved ones.

All tools and technology alter the range of our senses, including our animate perception—the degree to which we can sense and interact with the “expressive agency, or life” of another being. Tools can open, expand, or sharpen our senses, and they can also close, limit, or dull them, often at industrial scale. While a tree’s email address encourages us to see a tree as a pen pal, other tools may intentionally or unintentionally encourage us to treat a tree as a resource, asset, or weed without its own expressive agency.

This might begin with an innocent trade off: to expand our senses or abilities in one direction, we often accept limitations in another. For example, we want to make our environment safer or more comfortable, so we design tools that allow us to shape it more efficiently and untangle some of the inconvenient complexity of reality. We begin to define a border, a margin between the environment that is within our control and the other, wilder, more-than-human world. This in itself is a neutral activity—shaping our environment through “acts of transformation”, enchanting it with our own presence, is practical and often deeply meaningful:

When we cook things, we transform them. And any small acts of transformation are among the most human things we do. Whether it’s nudging dried leaves around a patch of cement, or salting a tomato, we feel, when we enter tiny bits of our human preference in the universe, more alive. -Tamar Adler, An Everlasting Meal

When done with care and a sense of the animate, these acts are what Christopher Alexander called “structure preserving transformations.” The process itself is an unfolding that carries the aliveness of the whole through (often dramatic) change. But as the border becomes stronger and our focus turns inward, we may find it harder to perceive the agency of the world as a whole and our participation in it. As our influence expands, we may start to see ourselves as the primary creators of the environment rather than part of it, and make even more tools that reinforce this perception.

This process becomes a wicked loop—a perception crisis—in which our perception shapes our tools and our tools shape our perception, each reinforcing the assumptions of the other. These tools may become disenchanted, limiting our sense of the magic in the world and our ability to participate in it. Disenchanted tools cut through the inconvenience of entangled complexity and promise (the illusion of) efficiency, economy, simplicity, and safety for the cost of alienation. Because they ignore entangled relationships, they can be adopted at the scale of corporations, countries, and civilizations, and gain the power to create or consume entire environments specifically for asset creation and extraction. As Anna Tsing writes in The Mushroom at the End of the World, disenchanted tools deployed at scale eventually leave behind only “weeds or waste”:

Alienation obviates living-space entanglement. The dream of alienation inspired landscape modification in which only one stand-alone asset matters; everything else becomes weeds or waste. When a singular asset can no longer be produced, a place can be abandoned. The timber has been cut; the oil has run out; the plantation soil no longer supports crops. The search for assets resumes elsewhere. Thus, simplification for alienation produces ruins, spaces of abandonment for asset production.

Knowing this, we might still accept the cost of disenchanted tools for the benefits they provide. However, their influence doesn’t stop at the forest border. Tools designed to reduce the more-than-human world to either assets or waste can encourage us to apply the same view to humans, ourselves. In Tools for Conviviality, Ivan Illich called these tools “industrial tools” in contrast with “convivial tools.” Convivial tools enable and expand the individual’s expressive agency, while industrial tools deny the expressive agency of their user and instead limit and direct their actions toward the industrial goal. Rather than the tool being an extension of the human’s senses and actions, the human becomes an extension of the tool. The tool treats the human as a resource and is designed to manage and direct the human’s performance rather than support the human’s own creative agency. Those who create or own the tools are elevated “above the API,” and those who are directed by the tools are “below the API.” When the combination of disenchanted and industrial tools deeply shape our perception, relationships, and communities, we risk losing sense of even our own animism and ability to participate in enchantment together. By consuming the forest margins to support our own conviviality, we end up making it more precarious.

In The Mushroom at the End of the World, Anna Tsing describes the curious world of the matsutake mushroom, a popular (and expensive) foraging prize that prefers highly specific growing conditions and resists cultivation. Oddly, matsutake grows eagerly in “human-disturbed” pine forests, especially those that were grown by humans for commercial logging and later abandoned—exactly the kind of environments that disenchanted, industrial tools leave behind. These forests were created and processed with a singular goal, to fuel and extend the logging industry operations and meet demand for building materials. When the economic or natural environment made the operation unsustainable and the assets were harvested, the forests were abandoned and became ruins. Now, this marginal land is a reminder that even when we act as though we are separate from nature, we are still fully participating as one part of the whole. The “human-disturbed” environment is exactly where the matsutake, and the Green Man, thrive.

The ruins of a roller coaster in an abandoned theme park in Japan photographed by Romain Veillon in a series of photos of abandoned places overtaken by nature.

The ruins of a roller coaster in an abandoned theme park in Japan photographed by Romain Veillon in a series of photos of abandoned places overtaken by nature.

In this context the Green Man may appear to be a warning that our tools are leading us toward ruin and that nature will inevitably cross the boundary to reclaim territory in the human world. But he is also a reminder that no matter how dull our senses are and how separate we assume we are, we are participating in entangled, contaminated, complex relationships. His anonymous presence in the margins has been mysterious and sometimes ominous, a nameless spirit with no known roots. But perhaps now that the entire planet is “human-disturbed,” he is re-emerging as a modern myth, to help us see the precariousness we’ve created, and encourage us toward enchantment:

Larrington takes the twenty-first-century scholar’s perspective on the Green Man: as a “vegetation god,” she insists, he has “been shown not to exist.” He was, rather, invented in 1939, “for a world which was beginning to need him, a world in which people were gradually realising how industrialisation was stealthily degrading our planet.” He came to represent “all that the modern world undervalues, excludes or lacks.” He doesn’t appear in stories, “except those invented for him by modern writers,” Larrington explains, but his “appearance, as a hybrid of man and plant, insists that humans are inextricably part of that natural world which we in the West are so keen to subjugate.” The Green Man may not be locatable in some named hill or brook, Larrington tells us, but he speaks to us profoundly in our time of ecological crisis. He is nowhere but everywhere.

Maybe he can help us learn how to “look around rather than look ahead,” how to refresh our animate perception, and see our entangled relationships more clearly. Maybe he can remind us that we can’t stand apart from the whole no matter how hard we try, so when we transform our environment we would be wise to do so with care and animate awareness. Maybe we can learn to make enchanted tools that help us participate in exchange, rather than attempt to preserve or subjugate:

Our relationship with the world is all wrong. You all know the story that got us here; it’s one of dominion and conquest. Our exploitation of natural resources was made possible by a set of beliefs, including what the non-human world is made of (inanimate matter) and what we can do with it (anything we like).

We see nature as being distinct from humanity and we believe it is our right and responsibility to save it–a more palatable outgrowth from the same foundations. I hear these assumptions humming under our apprehension of all three dark forests: the actual, the psychic and the digital. If we accept these forests as ecosystems rather than barren arenas for human exploits then we realise there is no place where the trees end and we begin. They are in your lungs and you are in theirs. You do not leave your dreams upon waking and the internet is not a separate place we visit: it is made of us. Thinking of the world as one thing and ourselves as another perpetuates our alienation. Ironically, those most invested in saving the world ensure the longevity of the attitude that destroys it.

This attitude must be sacrificed. We cannot think of The Dark Forest as a place we own, as a place separate from ourselves or something that we have ultimate responsibility for. We must see it for what it is: a complex ecosystem that we participate in and that shapes us just as much as we shape it.

Link encounters the Deku tree seedling

Link encounters the Deku tree seedling

A “word for the year” is a bundle of interconnected, layered themes, contexts, nudges, archetypes, hats, and lenses that serve as a “fuzzy contextual beacon” for the year ahead. Now that I think about it, a word is kind of like looking into the dark forest and seeing a will-o’-the-wisp marking a path in the distance, or like having Navi over your shoulder shouting “Hey! Listen!” when you need a hint or a reminder. The word stays with you, not as a goal to meet, but as an aid to navigating your own multi-faceted self reflection, development, and actualization.

As I wrote when I previously chose the word Gnome as a word for the year, I had first attempted to choose the word “magician.” I had noticed that in many ways I was holding back from fully embracing more fanciful, imaginative, and Romantic parts of myself, and I was discovering surprising new facets in my interest in practicing creativity. The layered themes of the word “magician” felt fitting, and I described wanting to “directly participate” in magic, to access my own arcane powers, and to “learn to enchant.” Enchantment became a useful shorthand for the quality I wanted to imbue in my creative practice—aliveness, wholeness, fluency and fluidity, and a quiet peace in the midst of transformation and even entropy.

However, I quickly realized this direct approach wasn’t what I expected. It was like trying to cast a spell at too high of a level—I thought I understood magic conceptually, but I lost the nuance of practice in misinterpretation and lack of hands-on experience. What I now call the “magician’s interlude” starkly revealed the old patterns I was clinging to that were no longer helpful in the relationships I care about—my family, friends, community, colleagues, and my own creative practice. While there were hints in the magician’s texts about participatory co-creation, lightheartedness, and non-linear transformations, a part of me focused on the allure of the magician’s remarkable powers—individual willpower as an arcane source and the ability to snap fingers to instantaneously turn intention into reality. I became even more frustrated when I experienced what I saw as procrastination or feeling stuck in my creative projects, and it became clear exactly how unsustainable raw willpower and burning out to serve external expectations were.

So, I took a detour through the Fungisphere with the invitation of the Gnome. The Gnome encouraged me to approach magic through the mushroom filled underdark rather than the overworld route, through an amalgamation of play, craft, and discipline, and through caring for the whole creative environment. All of this was a lot more fun, a lot more lovely, and a lot more peaceful than the forceful will of the magician in the tower. In the year of the Gnome, we moved to our house, and behind that house is an enchanted forest—a woodland border ravine with spruce, cedar, oak, and maple trees. I found myself starting to collect leaves and make drawings of them. I started using my enchanted tools (iPhone) to cast Identify on the plants in the garden and the neighborhood. Every square inch of the house, garden, and neighborhood held mystery and wonder. I was looking around rather than looking ahead. The Fungisphere gave me a high speed WiFi connection to the Wood Wide Web, and through this channel I began to sense the animate presence of the Green Man, the Oak King, Silvanus, the Great Deku Tree. I don’t actually know what I will encounter in the Year of the Enchanter, but I think that’s the whole point.

To notice when I’m trying to protect myself by taking total responsibility and “make something happen” through willpower. To “playfully co-create reality in collaboration with each other and the world.” To follow seemingly nonsensical, intuitive desires and detours to see where they lead.

We have to understand the difference between making things happen, trying to force things to happen, trying to do things with willpower and action, and understanding that when we’re in our home frequency, things magically happen. We just let things happen. That’s what it feels like to get out of your own way. –Maryam Hasnaa

To get my boots on and go for a walk. To enter the dark forest at the edges of comfortable creative practice. To notice the nuance between creative resistance and burnout from broken boundaries.

I frequently tramped eight or ten miles through the deepest snow to keep an appointment with a beech tree, or a yellow birch, or an old acquaintance among the pines.” –Henry David Thoreau

To feel feelings fully. To compost. To make of myself a sensitive recording plate.

The first lessons of drawing are lessons of looking: learning to look at another human being without expectation, to truly see what’s in front of you and to record that on the page. As you progress, you will realize that your depictions of people are not just records of something observed but of something experienced. –Jake Spicer

I chose my word with the wise guidance of the Choose One Word program by Dr. Jason Fox. I’m deeply grateful for the rich insights I found in this video series, and for the charming, caring, and generous space Jason created for self-knowledge, self-development, and self-actualization. I highly recommend trying it yourself.

I can’t pass pointing out that the last name of the city’s environmental portfolio chair is “Oke” and the last name of another councilor is “Wood”… ↩